You Can't Fix

What You Don't Understand

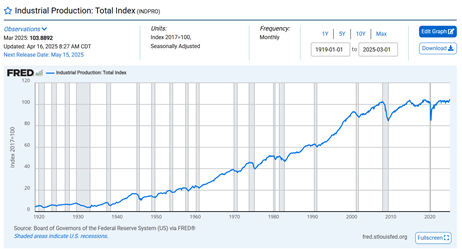

Welcome to the Asylum once again, my dear readers. This week, I want to discuss a misconception that almost everyone believes and repeats. Contrary to popular belief, American industry hasn’t been shipped offshore. America has more industrial production capacity than ever and produces more durable goods. I am not saying there are no gaps, because there are. We do not produce nearly enough microchips and other high-tech components. It is also true that new production has been expanded offshore since the 1980s, and since that time, factories have closed, but those closures did not impact America's industrial might. Please see the total industrial production index (here and here).

The myth of America losing its industrial production capacity comes from the fact that American industry changed radically from the 1980s to the mid-1990s. Before the 1990s, just about anyone with a high school diploma could get a union factory job, then spend the next 20 to 30 years bolting on the same part on an assembly line or doing some other repetitive task as the product moved by on the line, then retire with a pension and live happily ever after. The fact is, most of these jobs were not lost to Mexicans or Chinese, but to robots (here, here, and here). Robots don’t need shifts, produce far more, and maintain higher quality standards than human workers. The result is that most factories went from hundreds of line workers to tens of technicians, programmers, and other more technical people. Most of America’s industrial factory workers are white-collar rather than blue. Ultimately, the result is that we make more stuff for less money, which is good on the balance sheets. While most traditional industrial jobs disappeared, that process created positions for people to program, maintain, and operate robots.

The auto industry is the perfect example, once the company has a new fully automated plant that can produce 2- 3 times the number of vehicles as the older traditional plant (even if it has some automation) why not close the more traditional factory?

This wouldn’t have been a significant issue had there been no other important changes. In the previous century, America shifted away from agricultural jobs in the late 1800s, just as massively as factory jobs in the late 1900s. We didn’t starve because the technology that brought workers out of the field and into the factory allowed the remaining farms to grow massively and produce more for every acre utilized in agricultural production (here). This shift allowed for the total economic pie to get bigger, while everyone got wealthier. Farming more land with higher production made farmers richer, working a union factory job made city folks richer, and increasing the available goods and services made everyone wealthier. Unfortunately, other significant changes happened alongside the digital revolution that did not accompany the industrial revolution a century before.

The 1970s saw the rise of the Federal Regulatory State with the birth of OSHA in 1971, the EPA in 1970, CPSC in 1972, and dozens of others since (here and here). This explosion of executive oversight of business significantly increased the cost and time it took to build out factories in the United States, and more than anything, companies sought to open factories in other countries with less onerous regulations (here and here). Ultimately, if a company can spin up a new factory in 18-24 months in Mexico or China for half the cost of building one in 24-36 months for twice the price before the first worker enters the building due to regulatory compliance and then have to spend massive amounts of money every year on continued regulatory compliance, they will build out manufacturing overseas. This resulted in far fewer of the new technical factory jobs being generated here in the States (the line worker job is essentially dead and will never be back). Because the government cares about quantity over quality, we started hearing about the new service economy sometime in the late 1990s. To support this, both local and federal governments took steps to encourage the growth of these types of jobs. The problem is that most of these jobs are low-paying, low-skilled hospitality-type positions (here). These jobs are necessary to an extent. It is the economic equivalent to replacing all your daily calories with white sugar. Sure, you are getting sufficient calories, but they are not healthy or productive due to sugar in that quantity. It doesn’t matter that most of these positions are low-wage, dead-end, non-career type jobs. They are jobs.

The second thing that occurred in the 1970s is that (Say it with me. I can’t flog a dead horse alone.) on August 15th, 1971, Nixon rendered the US Dollar a fully fiat currency. As the massive debt accumulated from both the Vietnam War and the Great Society programs of 1964 unraveled quickly, we saw the enormous stagflation of the 1970s as more and more fiat was newly added to the economic system. Then, at various speeds since then, and at every slight slowdown, more and more unbacked currency was added, devaluing all that came before in an endless inflationary spiral. Interestingly, Carter had almost no control over the economy during his administration because he was elected in the heart of the inflation caused by Nixon, so that the warfare-welfare state could be supported. Then, Reagan also got pretty lucky with timing in that the initial inflationary shock ended in his first year, and he had a Federal Reserve Chairman with the courage to put the brakes on the printing press. While not perfect, it did extend to some degree the prosperity enjoyed by past generations. Unfortunately, from 1990 on, the presses haven’t really paused but only accelerated. This unprecedented inflation killed pensions, because unless you can’t go bankrupt (Government), it is impossible to set up a fund like a pension in a constant state of inflation over 10% (This is the real rate and higher here).

The bottom line is fiat-funded government spending, and the rise of the regulatory state (executive power the executive branch shouldn’t have here) are why the middle class is shrinking. My generation, Gen X, is the last with any chance of living out the old pattern, mostly because we came of working age at the start and could establish ourselves before things got super bad. Unfortunately, we are at the super bad part, and the middle-class dissolves more rapidly yearly. With all the talk of tariffs, the economy, and bringing back American industry, I felt it was essential to make sure folks know industry never really left, and the old ideas of working the line for 20-30 years and retiring are dead and long gone for the most part.

1 Timothy 5:17-18

17 Let the elders who rule well be considered worthy of double honor, especially those who labor in preaching and teaching. 18 For the Scripture says, “You shall not muzzle an ox when it treads out the grain,” and, “The laborer deserves his wages.”

God bless you!

-Sam